the Architecture

church history.. church history..

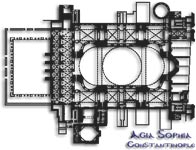

The new  Hagia

Sophia belongs to the transitional type of the domed basilica. Its

most remarkable feature is the huge dome supported by four massive piers,

each measuring approximately 100 sq. m. at the base. Four arches swing

across, linked by four pendentives. The apices of the arches and the

pendentives support the circular base from which rises the main dome,

pierced by forty single-arched windows. Beams of light stream through

the windows and illuminate the interior, decomposing the masses and

creating an impression of infinite space. Twelve large windows in two

rows, seven in the lower and five in the upper, pierce the tympana of

the north and south arches above the arched colonnades of the aisles

and galleries. The thrust of the dome is countered by the two half-domes

opening east and west, the smaller conchs of the bays at the four corners

of the nave, and the massive outside buttresses to the north and south. Hagia

Sophia belongs to the transitional type of the domed basilica. Its

most remarkable feature is the huge dome supported by four massive piers,

each measuring approximately 100 sq. m. at the base. Four arches swing

across, linked by four pendentives. The apices of the arches and the

pendentives support the circular base from which rises the main dome,

pierced by forty single-arched windows. Beams of light stream through

the windows and illuminate the interior, decomposing the masses and

creating an impression of infinite space. Twelve large windows in two

rows, seven in the lower and five in the upper, pierce the tympana of

the north and south arches above the arched colonnades of the aisles

and galleries. The thrust of the dome is countered by the two half-domes

opening east and west, the smaller conchs of the bays at the four corners

of the nave, and the massive outside buttresses to the north and south.

The esonarthex and exonarthex, to the west, are both roofed by cross-vaults.

Two roofed cochliae (inclined ramps). north and south of the esonarthex

Iead up to the galleries.

The vast rectangular atrium extending west of the exonarthex had a peristyle

along its four sides. At the center stood the phiale (fountain of purifications)

with the well-known inscription that could be read from left to right

and from right to left:

NIΨONANOMHMATAMHMONANOΨIN

"Cleanse our sins, not only our face"

The church measures 77 x 72 m. and the impressive huge dome soaring 62

m. above the floor has a diameter of about 33 m. According to R. van Nice,

a scholar well versed in the problems posed by the architecture and statics

of  Hagia

Sophia, the nave is 38.07 m. wide, slightly more than twice the width

of the aisles, which measure 18.29 m. each. The vertical planes formed

between the two north and the two south piers by the arcades of the aisles

and galleries and the tympana above them are aligned flush with the side

of the piers facing the nave. Thus, the mass of the piers is pushed aside

into the aisles and galleries. By this clever arrangement the bearing

structure is hidden from the eye, creating the impression that space expands

in all directions and that the dome floats in the air. Hagia

Sophia, the nave is 38.07 m. wide, slightly more than twice the width

of the aisles, which measure 18.29 m. each. The vertical planes formed

between the two north and the two south piers by the arcades of the aisles

and galleries and the tympana above them are aligned flush with the side

of the piers facing the nave. Thus, the mass of the piers is pushed aside

into the aisles and galleries. By this clever arrangement the bearing

structure is hidden from the eye, creating the impression that space expands

in all directions and that the dome floats in the air.

The vast expanse under the dome and the half-domes seems to expand

further: " The eye follows the vertical axisrising into immensity of main domeand moves longitudinally until it encounters apse sanctuary. The

eye follows the vertical axis, rising into the immensity of the main

dome, and moves longitudinally until it encounters the apse of the sanctuary"(Mavridis).

The capitals bearing Justinian's monogram are exquisitely carved producing

a lacework effect. The marble revetments of the piers and walls glow

with the beauty of their rare coloring. The imposing bronze doors are

adorned with the monograms of Theophilus and Michael among inscribed

prayers. Everything creates an impression of preciousness and perfect

harmony. The few but so important surviving mosaics disclose the awe

and diffidence of each epoch that did not dare or could not proceed

to decorate the church with an iconographic programm worthy of the monument's

fame.

By the end of the 5th century the basilical type of church had spread

over the entire Mediterranean region with the exception of a few centralized

buildings. From the early 6th century, however, the Christian world was

preparing the ground for a major change in art and particularly in architecture.

New methods of vaulting and statics were tried. Barrel-vaults. half-domes

and domes prevailed in building techniques. The one great problem which

found its solution in the age of Justinian was the transition from the

square to the circle. i.e. the raising of a circular dome over a square

base.

This new technical achievement, tried first in the church of St. George

at Ezra. Syria, then in that of the Sts. Sergius and Bacchus at Constantinople,

found its most perfect expression in the

Hagia

Sophia, this masterpiece of Christian architecture. Innumerable

descriptions praise the classical merit of the monument."The

spiritual character of Byzantine art found its completion in the Hagia

Sophia the spiritual character of byzantine art found its completion in the hagia sophia",

(Kalokyris). Polychrome marbles, elegant columns and fine wall revetments,

gold vessels and ornaments, exquisite mosaics, the huge dome, half-domes,

vaults and arches, the elaborately carved capitals, friezes and cornices,

the arcades, the one hundred windows and the interplay of light and

shade, all dissolve substance, filling the faithful with awe and delight

and revealing to the beholder the everlasting beauty of perfection. Hagia

Sophia, this masterpiece of Christian architecture. Innumerable

descriptions praise the classical merit of the monument."The

spiritual character of Byzantine art found its completion in the Hagia

Sophia the spiritual character of byzantine art found its completion in the hagia sophia",

(Kalokyris). Polychrome marbles, elegant columns and fine wall revetments,

gold vessels and ornaments, exquisite mosaics, the huge dome, half-domes,

vaults and arches, the elaborately carved capitals, friezes and cornices,

the arcades, the one hundred windows and the interplay of light and

shade, all dissolve substance, filling the faithful with awe and delight

and revealing to the beholder the everlasting beauty of perfection.

Some twenty years after the consecration of the church, a severe earthquake

caused serious damages to the dome and the eastern half-dome. During repairs

these structures partly collapsed, destroying the Lord's Table, the ciborium

and the ambo (May 7, 558). Reconstruction was entrusted to Isidorus the

Younger. The dome was rebuilt steeper and of lighter materials and the

supporting base was reinforced. The church was re-dedicated on December

23, 563.

From time to time Emperors repaired, restored and embellished the Great Church, or made generous donations, as it appears in the following list: Justin II (565-578) and empress Sophia, donations; Maurice (582-602) donations, in particular

a gold crown; Michael I Rangabe (811-813) donations; Basil I (867-886) repairs and possible the mosaic of the Theotokos in

the sanctuary apse; John

I Tsimisces (969-976) donations; Basil II (976-1025) repairs to

the dome and eastern apse that had been damaged by earthquakes in 989;

Roman III Argyrus (1028-1034)

decoration of the capitals with gold and silver; Constantine

IX Monomachus (1042-1055) and John

II Comnenus (1118-1143) donations of money and properties. Patriarch

George II Xiphilinus (1192-1199) is reported to have restored the interior

decoration: "He embellished anew and adorned the great church

restoring all the icons of the saints that are in it"

(Chronicle of George the Sinner, Migne, Vol. 110, 1237). The buttresses

at the east wall were erected in the reign of Andronicus

II Palaeologus (1282-1328).

The eastern part of the church and the mosaic of the Virgin in the apse

were seriously damaged in the earthquake of 1346.

|