|

Movement

|

Doctrine

and practice

Orthodox Church stands in historical continuity with the Christian

communities of the eastern Mediterranean and which spread by missionary

activity throughout eastern Europe. The word orthodox (from Greek,

"right-believing") implies doctrinal consistency with apostolic

truth. The Orthodox church has also established communities in Western

Europe, the western hemisphere, and, in Africa and Asia, and it currently

has an estimated 200 million adherents throughout the world.

Other designations, such as Orthodox Catholic (the word καθολικός means

universal, i.e. catholic), Greek Orthodox, and Eastern Orthodox, are

also used in reference to the Orthodox church.

Structure and organisation

The Orthodox church is a fellowship of independent churches. Each is

autocephalous, that is, governed by its own head bishop. These autocephalous

churches share a common faith, common principles of church policy and

organisation, and a common liturgical tradition. Only the languages

used in worship and minor aspects of tradition differ from country to

country. The head bishops of the autocephalous churches may be called

patriarch, metropolitan, or archbishop. These prelates are presidents

of Episcopal synods, which, in each church, constitute the highest canonical,

doctrinal, and administrative authority. Among the various Orthodox

churches there is an order of precedence, which is determined by history

rather than by present-day numerical strength.

The Orthodox Church is a fellowship of “autocephalous” churches (governed

by their own head bishops), with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

holding titular or honorary primacy. The number of autocephalous churches

has varied in history. Today there are many: the Church of Constantinople,

the Church of Alexandria (Egypt), the Church of Antioch (with headquarters

in Damascus, Syria), and the churches of Jerusalem, Russia, Ukraine,

Georgia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Albania, Poland,

the Czech and Slovak republics, and America.

There are also “autonomous” churches (retaining a token canonical dependence

upon a mother see) in Crete, Finland, and Japan. The first nine autocephalous

churches are headed by “patriarchs,” the others by archbishops or metropolitans.

These titles are strictly honorary.

The order of precedence in which the autocephalous churches are listed

does not reflect their actual influence or numerical importance. The

patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch, for example,

present only shadows of their past glory. Yet there remains a consensus

that Constantinople's primacy of honour, recognized by the ancient canons

because it was the capital of the ancient empire, should remain as a

symbol and tool of church unity and cooperation. The modern pan-Orthodox

conferences were thus convoked by the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople.

Several of the autocephalous churches are de facto national churches,

by far the largest being the Russian Church; however, it is not the

criterion of nationality but rather the territorial principle that is

the norm of organization in the Orthodox Church.

Since the Russian Revolution there has been much turmoil and administrative

conflict within the Orthodox Church. In western Europe and in the Americas,

in particular, overlapping jurisdictions have been set up and political

passions have led to the formation of ecclesiastical organizations without

clear canonical status. Though it has provoked controversy, the establishment

(1970) of the new autocephalous Orthodox Church in America by the patriarch

of Moscow has as its stated goal the resumption of normal territorial

unity in the Western Hemisphere.

top ^

The Patriarch of Constantinople

A "primacy of honour" belongs to the patriarch of Constantinople

, because the city was the

seat of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, which between AD 320

and 1453 was the centre of Eastern Christendom. The canonical rights

of the patriarch of Constantinople were defined by the councils

of Constantinople (381) and Chalcedon (451). In the 6th century he also

assumed the title ecumenical patriarch. Neither in the past, nor in

modern times, however, has his authority been comparable to that exercised

in the West by the Roman pope: the patriarch does not possess administrative

powers beyond his own territory, or patriarchate, and he does not claim

infallibility. His position is simply a primacy among equals. The other

churches recognise his role in convening and preparing pan-Orthodox

consultations and councils. His authority extends over the small (and

rapidly vanishing because of the repressions from the turkish government)

Greek communities in present day Turkey; over dioceses situated in the

Greek islands and in northern Greece; over the numerous Greek-speaking

communities in the United States, Australia, and Western Europe; and

over the autonomous church of Finland.

top ^

Other Ancient Patriarchates

Three other ancient Orthodox patriarchates

owe their positions to their distinguished pasts: those in Alexandria,

Egypt; Damascus, Syria (although the incumbent carries the ancient title

patriarch of Antioch); and Jerusalem. The patriarchs of Alexandria and

Jerusalem are Greek-speaking; the patriarch of Antioch heads a significant

Arab Christian community in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

top ^

Russian and Other Orthodox Churches

The patriarchate of Moscow and all Russia is the largest Orthodox church

today by far, having survived a difficult period of persecution after

the Russian Revolution of 1917. It occupies the fifth place in the hierarchy

of autocephalous churches, followed by the patriarchies of the Republic

of Georgia, Serbia , Romania, and Bulgaria. The nonpatriarchal churches

are, in order of precedence, the archbishops of Cyprus,

Athens, and Tirana (established 1937, this see was suppressed during

Communist rule), as well as the metropolitanates of Poland, the Czech

Republic, Slovakia, and America.

top ^

Doctrine

In its doctrinal statements and liturgical texts, the Orthodox church

strongly affirms that it holds the original Christian faith, which was

common to East and West during the first millennium of Christian history.

More particularly, it recognises the authority of the ecumenical

councils at which East and West were represented together. These

were the councils of Nicaea

I (325), Constantinople I (381), Ephesus (431),

Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople

III (680), and Nicaea

II (787). Later doctrinal affirmations by the Orthodox church

for instance, the important 14th-century definitions concerning communion

with God are actually developments of the same original faith of the

early church.

top ^

Tradition

The concern for continuity and tradition, which is characteristic of

Orthodoxy, does not imply worship of the past as such, but rather a

sense of identity and consistency with the original apostolic witness,

as realised through the sacramental community of each local church.

The Holy Spirit, bestowed on the church at Pentecost, is seen

as guiding the whole church "in all truth" (John 16:13).

The power of teaching and guiding the community is bestowed on certain

ministries (particularly that of the bishop of each diocese) or is manifested

through certain institutions (such as councils). Nevertheless, because

the church is composed not only of bishops, or of clergy, but of the

whole laity as well, the Orthodox church strongly affirms that the guardian

of truth is the entire "people of God".

This belief that truth is inseparable from the life of the sacramental

community provides the basis for the Orthodox understanding of the apostolic

succession of bishops: consecrated by their peers and occupying the

"place of Christ" at the Eucharistic meal, where the church

gathers, bishops are the guardians and witnesses of a tradition that

goes back, uninterrupted, to the apostles and that unites the local

churches in the community of faith.

top ^

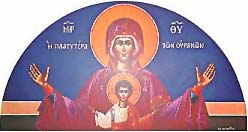

Christ and Panagia Mary

The ecumenical councils of the first millennium defined the basic Christian

doctrines on the Trinity, on the unique Person and the two natures of

Christ and on his two wills, expressing fully the authenticity and fullness

of his divinity and his humanity. These doctrines are forcefully expressed

in all Orthodox statements of faith and in liturgical hymns. Also, in

light of this traditional doctrine on the Person of Christ, the Virgin

Mary is venerated as Mother of God. Further Mariological developments,

however, such as the more recent Western doctrine of the immaculate

conception of Mary, are foreign to Orthodoxy. Mary's intercession is

invoked because she was closer to the Saviour than anyone else and is,

therefore, the representative of fallen humanity and the most prominent

and holiest member of the church.

top ^

Sacraments

The doctrine of seven sacraments is generally accepted in the Orthodox

church, although no ultimate authority has ever limited the sacraments

to that number. The central sacrament is the Eucharist;

the others are baptism, normally by immersion;

confirmation, which follows baptism immediately

in the form of anointment with chrism; penance;

Holy Orders; marriage; and anointment of the sick. Some medieval authors

list other sacraments, such as monastic tonsure, burial, and the blessing

of water.

top ^

Celibacy

Orthodox canonical legislation admits married men to the priesthood.

Bishops, however, are elected from among celibate or widowed clergy.

top ^

Practices

According to a medieval chronicle, when representatives of the Russian

prince Vladimir visited the Hagia

Sophia (Church of the Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople in 988, they

did not know "whether they were in heaven, or on earth". Most

effective as a missionary tool, the Orthodox liturgy has also been,

throughout the centuries of Muslim rule in the Middle East, an instrument

of religious survival. Created primarily in Byzantium and translated

into many languages, it preserves texts and forms dating from the earliest

Christian church.

top ^

Liturgy

The most frequently used Eucharistic rite is traditionally

attributed to St John Chrysostom. Another Eucharistic liturgy,

celebrated only ten times during the year, was created by St Basil

of Caesarea. In both cases, the Eucharistic prayer of consecration

culminates with an invocation of the Holy Spirit (epiclesis)

upon the bread and wine. Thus, the central mystery of Christianity is

seen as being performed by the prayer of the church and the action of

the Holy Spirit, rather than by "words of institution", pronounced

by Christ and repeated vicariously by the priest, as is the case in

Western Christendom.

One of the major characteristics of Orthodox worship is a great wealth

of hymns, which mark the various liturgical cycles (see Liturgy).

These cycles, used in sometimes complicated combinations, are the daily

cycle, with hymns for vespers, compline, the midnight prayer, matins,

and the four canonical hours; the paschal cycle, which includes the

period of Lent before Easter and the 50 days separating Easter and Pentecost

and which is continued throughout the Sundays of the year; and the yearly,

or sanctoral, cycle, which provides hymns for immovable feasts and the

daily celebration of saints. Created during the Byzantine Middle Ages,

this liturgical system is still being developed through the addition

of hymns honouring new saints. Thus, two early missionaries to Alaska,

St Herman and St Innocent, were recently added to the catalogue of Orthodox

saints.

top ^

Icons

Inseparable from the liturgical tradition, religious art is seen by

Orthodox Christians as a form of pictorial confession of faith and a

channel of religious experience. This central function of religious

images (icons) unparalleled in

any other Christian tradition received its full definition following

the end of the iconoclastic movement

in Byzantium (843). The iconoclasts invoked the Old Testamental prohibition

of graven images and rejected icons as idols. The Orthodox theologians,

on the other hand, based their arguments on the specifically Christian

doctrine of the incarnation: God is indeed invisible and indescribable

in his essence, but when the Son of God became man, he voluntarily assumed

all the characteristics of created nature, including describability.

Consequently, images of Christ, as man, affirm the truth of God's real

incarnation. Because divine life shines through Christ's risen and glorified

humanity, the function of the artist consists in conveying the very

mystery of the Christian faith through art. Furthermore, because the

icons of Christ and the saints provide direct personal contact with

the holy people represented on them, these images should be objects

of "veneration" (proskynesis), even though "worship"

(latreia) is addressed to God alone. The victory of this theology

over iconoclasm led to the widespread use of iconography in the Christian

East and also inspired great painters most of whom remain anonymous

in producing works of art that possess spiritual as well as artistic

value.

top ^

History

Because a majority of non-Greek-speaking Christians of the Middle East

rejected the Council of Chalcedon and because, after the 8th century,

most of the area where Christianity was born remained under the rule

of Muslims, the Orthodox patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem

kept only a shadow of their former glory. Constantinople, however, remained,

during most of the Middle Ages, by far the most important centre of

Christendom. The famous Byzantine missionaries, St Cyril and St

Methodius, translated (864) Scripture and the liturgy

into Slavonic, and many Slavic nations were converted to Byzantine Orthodox

Christianity. The Bulgarians, people of Turkic stock, embraced

it in 864 and gradually became Slavicized. The Russians, converted

in 988, remained in the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the patriarchate

of Constantinople until 1448. The Serbs received ecclesiastical

independence in 1219, although they have been under strong influence

of the Orthodox Church for centuries.

top ^

Schism

Tensions periodically arose between Constantinople and Rome after the

4th century. After the fall of Rome (476) to Germanic invaders, the

Roman pope was the only guardian of Christian universalism in the West.

He began more explicitly to attribute his primacy to Rome's being the

burial place of St Peter, whom Jesus had called the "rock"

on which the church was to be built (see Matthew 16:18). The Eastern

Christians respected that tradition and attributed to the Roman bishop

a measure of moral and doctrinal authority. They believed, however,

that the canonical and primatial rights of individual churches were

determined above all by historical considerations. Thus, the patriarchate

of Constantinople and its own position had to be determined by the fact

that Constantinople, the "new Rome", was

the seat of the emperor and the Senate.

The two interpretations of primacy "apostolic" in the West,

"pragmatic" in the East coexisted for centuries, and tensions

were resolved in a conciliar way. Eventually, however, conflicts led

to permanent schism. In the 7th century the universally accepted creed

was interpolated in Spain with the Latin word filioque,

meaning "and from the Son", thus rendering the

creed as "I believe … in the Holy Spirit … who

proceeds from the Father and the Son". The interpolation,

initially opposed by the popes, was promoted in Europe by Charlemagne

(crowned emperor in 800) and his successors. Eventually, it was also

accepted (in around 1014) in Rome. The Eastern church, however,

considered the interpolation heretical, as it was. Moreover, other issues

became controversial: for instance, the ordination of married men to

the priesthood and the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist. Secondary

in themselves, these conflicts could not be resolved because the two

sides followed different criteria of judgement. The papacy considered

itself the ultimate judge in matters of faith and discipline, whereas

the East invoked the authority of councils, where the local churches

spoke as equals.

It is often assumed that the anathemas exchanged in Constantinople

in 1054 between the patriarch Michael Cerularius and papal

legates marked the final schism. The schism, however, actually took

the form of a gradual estrangement, beginning well before 1054 and culminating

in the sack of Constantinople

by western Crusaders in 1204.

In the late medieval period, several attempts made at reunion, particularly

in Lyons (1274) and in Florence (1438-1439), ended in failure. The papal

claims to ultimate supremacy could not be reconciled with the conciliar

principle of Orthodoxy, and the religious differences were aggravated

by cultural and political misunderstandings.

After the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453, they recognised

the ecumenical patriarch of that city as both the religious and the

political spokesman for the entire Christian population of the Turkish

empire. The patriarchate of Constantinople, although still retaining

its honorary primacy in the Orthodox church, ended as an ecumenical

institution in the 19th century when, with the liberation of the

Orthodox peoples from Turkish rule, a succession of autocephalous

churches were 1833, Romania (1864), Bulgaria (1871), and Serbia

(1879).

The Orthodox church in Russia declared its independence from Constantinople

in 1448. In 1589 the patriarchate of Moscow was established and formally

recognised by Patriarch Jeremias II of Constantinople. For the Russian

church and the tsars, Moscow had become the "third Rome",

the heir to the imperial supremacy of ancient Rome and Byzantium. The

patriarchate of Moscow never had even the sporadic autonomy of the patriarchate

of Constantinople in the Byzantine Empire. Except for the brief reign

of Patriarch Nikon in the mid-17th century, the patriarchs of Moscow

and the Russian church were entirely subordinate to the tsars. In 1721,

Tsar Peter the Great

abolished the patriarchate altogether, and thereafter the church was

governed through the imperial administration. The patriarchate was re-established

in 1917, at the time of the Russian Revolution, but the church was violently

persecuted by the Communist government. As the Soviet regime became

less repressive and, in 1991, broke up, the church showed signs of renewed

vitality. (The Orthodox church in Eastern Europe had a similar but foreshortened

history, restricted by Communist governments after World War II but

gaining freedoms in the late 1980s.)

top ^

Relations with Other Churches

The Orthodox church has been the organic continuation of the original

apostolic community and is holding a faith fully consistent with the

apostolic message. Orthodox Christians have, however, adopted different

attitudes through the centuries towards other churches and denominations.

In areas of confrontation, such as the Greek islands in the 17th century,

or the Ukraine during the same period, defensive Orthodox authorities,

reacting against active proselytism by Westerners, declared Western

sacraments invalid and demanded rebaptism of converts from the Roman

or Protestant communities. The same attitude prevails, today, in some

circles in Greece.

Always rejecting doctrinal relativism and affirming that the goal of

ecumenism is the full unity of the faith, Orthodox churches have been

members of the World Council of Churches since 1948. Orthodox generally

recognise that, before the establishment of full unity, a theological

dialogue leading in that direction is necessary and that divided Christian

communities can cooperage and provide each other with mutual help and

experience, even if sacramental intercommunion, requiring unity in faith,

appears to be distant.

The Protestant majority in the World Council of Churches has occasionally

made Orthodox participation in that body awkward, and the ecumenical

attitude adopted during the reign of Pope John XXIII by the Roman Catholic

church (which does not belong to the council) has been welcomed by Orthodox

officials and has led to new and friendlier relations between the churches.

Orthodox observers were present at the sessions of the Second Vatican

Council (1962-1965), and several meetings took place between popes Paul

VI and John Paul II on the one side, and patriarchs Athenagoras

and Demetrios on the other. In another symbolic gesture, the

mutual anathemas of 1054 were lifted (1965) by both sides. The

two churches have established a joint commission for dialogue between

them. Representatives met on at least 11 occasions between 1966 and

1981 to discuss differences in doctrine and practice. The claim

to authority and infallibility made by the pope is generally seen

as the primary obstacle to full reconciliation.

top ^

|